IFSR Newsletter 1993 Vol. 12 No. 2 August

Professor Dr. Magoroh Maruyama, Tokyo, IFSR Newsletter 1993 No. 2 (30) August

Prof. Dr. Magoroh Maruyama

School of lnternational Politics, Economics and Business,

Shibuya 4-4-25, Shibuya-Ku,Tokyo 150, Japan

Individual epistemological and psychological heterogeneity exists in every culture. An individual type that is found in any one of them also occurs in the others. Various traits are used to characterize the diverse types. For example, one kind of person prefers to learn by experiencing and perceiving things in a given context (the Japanese method of training), whereas another teams better by a sequenced transmission of information which is divided into categories and arranged hierarchically into topics and subtopics (predominant in the USA):

Cultural differences involve the ways in which a type becomes dominant and utilizes, suppresses or transforms other types. Nondominant types may survive in niches, in disguise or in repression, or they might rebel or emigrate. Cross-cultural data can be analyzed with the help of this new conceptual and methodological framework.

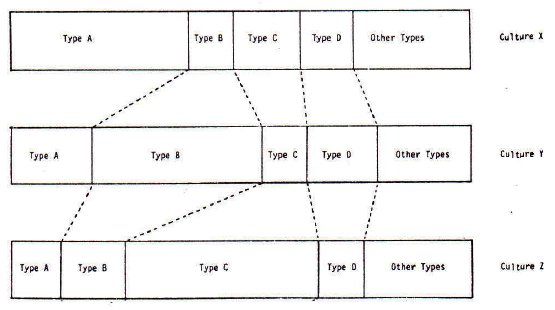

Until now, the most frequent method for cross-cultural study has been to compare the test score means of various countries to see whether there is a statistically significant difference between them. This procedure is based on the assumption that each country is homogeneous except for a statistical spread around the mean (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Homogenistic View of Cultures, Prof. Dr. Magoroh Maruyama, Tokyo, IFSR Newsletter 1993 Vol. 12 No. 2 (30) August

However, individual epistemological heterogeneity has been found to exist in each culture (Maruyama 197 4, 1980, Harvey 1966). Any type that is found in one of them occurs in others too (Maruyama 1974, 1980, 1993), as is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Individual Heterogeneity across cultures, Prof. Dr. Magoroh Maruyama, Tokyo, IFSR Newsletter 1993 Vol. 12 No. 2 (30) August

In many cases non-dominant types are covert, i.e. they are disguised or repressed. That means that upon questioning many individuals claim to be of the dominant type, although they don’t really fit into it.

The concept of individual heterogeneity across cultures (IHAC)can be extended to mental and behavioral aspects other than epistemological types. This new framework will necessitate basic revisions in many of the theories in social sciences and psychology. It will also generate new methodologies.

Moreover, many of the data collected in the past can be re-analyzed if the raw s@res are still available. Of all the various kinds of psychological examinations, aesthetic preference tests are expected to show the least amount of repression. For this reason, let us take one of them as an example; the theoretical rationale for it has been explained elsewhere (Maruyama 1992).

Figure 3: Examples of TOB patterns, Prof. Dr. Magoroh Maruyama, Tokyo, IFSR Newsletter 1993 Vol. 12 No. 2 (30) August

Each TOB pattern consists of a 4 by 4 grid composed of 16 squares; some of them are black and others are white. There ate 216 = 65,596 possible TOB patterns. TOB stands for Tokyo, Budapest and Bruxelles, where the first test run took place. The subjects rated each of them in respect to ’18 adjective pairs on a 7-point scale.

In most studies, adjective pairs are correlated and factor-analyzed. But in the current one, the stimuli (the patterns) are correlated and factor-analyzed to identify the aesthetic preference types. As a simplified example, let us take the adjective pair “l like / I do not like”. In

the factor analysis, stimuli dimensions are identified. An individual’s aesthetic preference type is determined on the basis of his choices.

In the test run, spurious factors were found. Some of the TOB patterns turned out to have symbolic significance in certain countries, so that the subjects were responding to that rather than to the aesthetic quality. Others had representational meaning. An example of a symbol is the Swastika. Representational meanings are “dog looking back”, “bird’, “prison”. Patterns which were found to be symbolic or representational were not used in the determination of aesthetic preference.

The new analysis can proceed in the following sequence: (1) Eliminate the stimuli which have symbolic or representational meanings; (2) Find stimuli-dimensions and individual types in each country; (3) Check whether the results are similar across cultures; (4a) If they are, combine the raw scores from all countries, then factor-analyze the stimuli to find international stimuli-dimensions and international individual types; (4b) l, they are not similar, reject IHAC for his adjective pair or for this set of TOB figures, and try other adjective pairs or other sets of figures; (5a) If IHAC can’t be shown, reject IHAC for this type of test; (5b) On the other hand if IHAC is confirmed, then we move onto other questions such as longitudinal factors, i.e. changes within an individual as he progresses, from childhood to adulthood; (6a) These, if found, may be due to maturation, which is common in all countries, or due to the influences from the mainstream type in the form of socialization, acculturation, marginalization, ostracism, sublimation, repression, identification, etc., which vary from culture to culture. We need many tests to arrive at well-founded conclusions.

IHAC is a new concept. It has been confirmed in respect to epistemological types, and it can be extended to other fields of social sciences and psychology. This will make it necessary to revise many of the current theories.

REFERENCES:

- Harvey, O.J. 1966. Experience, Structure and Adaptability. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Maruyama, M. 1974. Paradigmatology and its Application to Cross-disciplinary, Crossprofessional and Cross-cultural Communication. Cybernetica 1 7:1 36-1 56; 237 -281.

- Maruyama, M. 1980: Mindscapes and Science Theories. Current Anthropology 21 :589-599.

- Maruyama, M. 1992: Entropy, Beauty and Eumorphy. Cybernetica 35:1 95-206.

- Maruyama, M. 1993. Mindscapes, lndividuals and Cultures in Managemenl. Journal of Management Inquiry 2:1 40-1 55.