IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

St. Magdalena, Linz, Austria, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

After the Conversations in 2008 and 2010 where we looked at the status of Systems Sciences and their inner relationships this year we choose to look into the future. We recognized that there are different path into the future and that System Sciences as a discipline have to make some choice.

The Fuschl Conversations were established by the IFSR in 1980, primarily under the guidance of Bela H. Banathy, as an alternative to traditional conferences. A number of systems professionals found that they were disillusioned with a format in which the majority of the time was spent on papers being read or presented to passive listeners, with minimal time for discussion and interaction about the ideas. As described by Bela, they were to be:

- a collectively guided disciplined inquiry,

- an exploration of issues of social/societal significance,

- engaged by scholarly practitioners in self-organized teams,

- on a theme for their conversation selected by participants,

- initiated in the course of a preparation phase that leads to an intensive learning phase.

In 2012 the overarching theme for the conversation was how to reposition systems thinking in a changing world both with respect to scientific research and practical applications, in view of historical roots and the precarious situation of our environment. Hence the title “Systems and Science at Crossroads”.

The deliberations of the 4 teams supported the over-all theme in different ways:

Team 1: Revisiting the socio-ecological, social-technical and socio-psychological perspectives

Team 2: Science II: Science Too!

Team 3: Designing Learning Systems for Global Sustainability

Team 4: Towards a common language for systems praxis.

16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

We chose a different location again: the seminar hotel St. Magdalena on the outskirts of Linz, Austria. because we rightly believed that it was even better suited to the purpose of a conversation than the previous locations, and we were right.

The proceedings of the 2012 Conversation will be published both in hardcopy and by making them available on the IFSR Website. The proceedings will contain extensive reports from the four teams together with a few individual position papers detailing some of the deliberations of the team. A short preview of the outcome of the 4 teams are included in this Newsletter.

In addition to the proceedings we will also produce a ‘supplement’ which will contain additional material pertinent to the deliberations of the teams, additional material and/or more extensive reports.:

References:

Proceedings: Chroust, G. & Metcalf, G., editors (2012). Systems and Science at Crossroads – Sixteenth IFSR Conversation. Inst. f. Systems Engineering and Automation, Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria, SEA-SR-32, Sept. 2012 and [http://ifsr.ocg.at/world/files/$12m$Magdalena-2012-proc.pdf].

Supplement: Chroust, G. & Metcalf, G., editors (2012). Systems and Science at Crossroads – Sixteenth IFSR Conversation – Supplement. Inst. f. Systems Engineering and Automation, Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria, SEA-SR-32, Sept. 2012 and [http://ifsr.ocg.at/world/files/$12n$Magdalena-2012-supp.pdf].

Team 1: Revisiting the socio-ecological, social-technical and socio-psychological perspectives:

David Ing, CND ( isss@daviding.com )

Merrilyn Emery , AUS ( memery9@bigpond.com )

Debora Hammond , USA ( hammond@sonoma.edu )

Gary Metcalf , USA ( gmetcalf@interconnectionsllc.com )

Minna Takala , FIN ( minliitakala@gmail.com )

The Conversation within Team 1 began around a general triggering question: “In which ways is the Tavistock legacy still relevant, and which ways might these ideas be advanced and/or refreshed (for the globalized/service economy)?”

Dr. Merrilyn Emery, Team 1: Revisiting the socio-ecological, social-technical and socio-psychological perspectives, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

The thought at the time that the team was being formed was that the legacy of Tavistock and the material that came out of it were quite well known, but that the ideas had fallen out of use and possibly even currency. Through the contributions of Merrelyn Emery to the team, it became apparent very quickly that there were many gaps in information (at least by the other four team members), and varying interpretations of both the history and the theories. That turned the focus for the first part of the week into clarifying and correcting what was known and understood.

Much of the history of Tavistock, and many articles by its members, can be found in the online version of the Tavistock Anthology: http://www.moderntimesworkplace.com/archives/archives.html. Seeing articles written to capture ideas formally, in retrospect, though, gives little indication about how the ideas came to be, or of the relationships between the people involved. There was, for instance, a great deal of international exchange and collaboration which helped to develop the concepts associated with socio-technical systems, which happened in and around professional meetings and conferences. This included people such as Russ Ackoff, West Churchman, and Ross Ashby, in addition to Eric Trist, Fred Emery, and others who are typically associated with the work.

In learning more of the history it became clear that much of what was common knowledge for the people involved has been lost along the way since then. Kurt Lewin, for instance, is often associated with the concepts. His main contributions to this work, though, were through his research in the 1930s into principles of democracy, which helped to form the theoretical basis for the design principles of autocracy and self-managing, democratic groups. And while Bertalanffy is the name associated with open systems for most people today, as Merrelyn explained, “everyone had read Andras Angyal, and almost no one [in those groups] spoke of Bertalanffy.”

, Team 1: Revisiting the socio-ecological, social-technical and socio-psychological perspectives, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

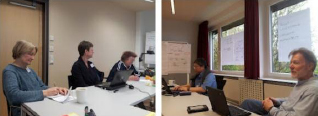

More of the week was spent digging into the basic constructs, understanding, for instance, exactly what was meant by Design Principle 1 (DP1) and Design Principle 2 (DP2), and what distinguished them from each other. There were also questions about how the Design Principles related to the different environments which had been described (Types 1 through 4).

It became clearer through discussion that the term “environment” had a number of different meanings in different contexts. The immediate work environment for an organization, for instance, is usually the “task environment.” The primary concept of environment, which comes from the work done by Emery & Trist (1965) is the “global social environment” – those elements which affect the relationships and functioning of the system in question most relevantly. It is explored in the Search conference.

Team 1: Revisiting the socio-ecological, social-technical and socio-psychological perspectives, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

As the week progressed the team moved from a focus on history and theory (though those continued to be revisited) to questions about where and how the principles showed up today, in different kinds of organizations and circumstances. Indeed, many of the early examples where self-managing work groups had been instituted no longer existed. After it was understood that the DP2 structure needed to be incorporated into the legal structure of the organization, the new structure remained intact and functioning.

This led to questions about transitions of structures within and between organizations. [It seemed probable that] Some work groups (e.g. some kinds of start-ups) began as self-managing organizations and became more hierarchical as they grew and evolved. Sometimes large corporations or projects experimented with such structures in their efforts towards innovation. (A specific example discussed was the building of Terminal 5 at Heathrow Airport, which seemed to function as a DP2 structure throughout the construction phase, but then dissolved entirely when it was handed over to operations, which was a DP1 structure.)

By the end of the week there were, as always, more new questions and possibilities than final conclusions and answers. It provided, however, a strong foundation on which more research into self-managing workgroups and organizations can be based.

Table 1, Team 1: Revisiting the socio-ecological, social-technical and socio-psychological perspectives, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

Team 2: Science II: Science Too!

Stuart Umpleby , USA (umpleby@gmail.com )

Jerry Chandler , USA ( Jerry_LR_Chandler@me.com )

Allenna Leonard (CND) allenna_leonard@yahoo.com

Michael Lissack , USA ( lissack@buy-in-naples.com )

Hellmut Loeckenhoff , D (loeckenhoff.hellk@t-online.de )

Tatyana Medvedeva , RU ( tmedvedeva@mail.ru )

Leonie Solomon , AUS ( leonie.solomons@gmail.com )

We began by raising issues such as: social science practitioners express frustrations and/or limitations with Science 1, general needs of a philosophy/epistemology of science, specific needs for a hypothetical science II, and what would that science ii include? We then defined frustrations and limitations regarding Science I (as expressed by individual members of the team): methodological misfits, reliable prediction is not always possible. our ability to “see” and “express” certain phenomena is restricted by science in use, the experience of “x” is not the same as the label “x”, and ceteris paribus is nonsense.

Our discussion then turned to the philosophy of science as used. We discussed that articulations of examples are most commonly physics based, despite the claims by physicists, other sciences cannot be reduced to physics or its equivalents without raising issues of both epistemology and ontology, other sciences have unique requirements demanding exact articulations, and that systems composed of thinking elements should not be described using methods developed for systems with non-thinking elements. This led to the idea that deficiencies in the philosophy of physics generate frustrations with the role of observers, the role of emergence, the role of habitus (i.e. the social, cultural, cognitive, historical, contextual milieu) and ambiguity of number symbols (whole versus continuous). We then observed that we saw no place for reflexivity and that “physics envy” was not appropriate for many other fields (e.g. chemistry, biology, social sciences…..).

Team 2: Science II: Science Too!, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

This allowed us to discuss some more general needs:

- Basis for social sciences and design (pragmatic assumptions)

- Need to deal with ideas and communication in social systems

- Philosophy of Science needs expansion

- Paths to potential logics of social sciences

- What is the basic unit (individual, group, set, dynamic, environment, etc.?)

- To separate biomedical concepts from social science concepts (e.g. the patient-physician relationship)

Which, in, turn led to some preliminary conclusions:

- Science II will require different languages than are commonly used in Science I

- Science II will require different frameworks of thinking

- Meta-level thinking as an opportunity

- Need for new strategies of simplification so as to meet requisite variety

- Science needs to change as the world changes

- New ontology and epistemology

- More transparency (to open the action and option space)

- Trans-disciplinarity as a shared basis for cross disciplinary conversations

- Formulate knowledge as methods as well as theories (include the observer)

We concluded that Science II needs to enrich the systems approach and reconcile the Eastern and Western approaches. Science II demands narratives (as shown by example of medical heuristics, e.g. narratives told by physicians to patients). Science II includes reflexive anticipation, and it demands more variety in describing homeostats and balance relationships and in ways to express circular causality. For managers, Science II demands that the very notion of “best practices” needs to be re-examined.

Our full report is on-line at http://isce.edu/ifsr.pdf

Figure 1: All statements are made by an observer (Maturana), Team 2: Science II: Science Too!, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

Team 3: Designing Learning Systems for Global Sustainability

“Ramping up for the ISSS 2013 Conference in Viet Nam.”

Stefan Blachfellner , AT ( Stefan@blachfellner.com )

Alexander Laszlo , USA ( alexander@syntonyquest.org )

Mary Edson , USA ( maredson.s3@gmail.com )

Ockie Bosch , AUS ( ockie.bosch@adelaide.edu.au )

Violeta Bulc , SL ( violeta.bulc@vibacom.si )

Leonard Allenna, CND ( allenna_leonard@yahoo.com )

Nam Nguyen , AUS ( nam.nguyen@adelaide.edu.au )

George Por , UK ( george@community-intelligence.com )

Jennifer Wilby , UK ( isssoffice@dsl.pipex.com

George Por, UK (george@community-intelligence.com, via Skype)

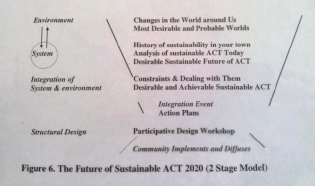

Figure 1: The Working Model, Team 3: Designing Learning Systems for Global Sustainability, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

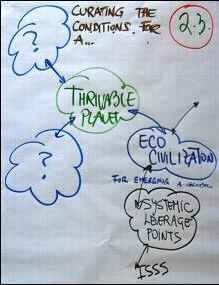

Our team worked on the practical design challenge of creating a series of related international events that address issues of liveability and thrivability in terms of systemic socio-ecological innovation. To do this, we focused at two systemic levels of intervention: at one level (which became the meta-level), we focused on curating the conditions for a thrivable planet. This was the larger vision – the idealized design objective that allowed us to contemplate a variety of pathways to address this objective. In this sense, it served as a design attractor for our work. We then chose to focus upon one feasible and realizable pathway that could serve as a functional prototype for addressing the meta-level objective. The 57th Meeting and Conference of the ISSS, set for Viet Nam in July of 2013, was selected to serve as the systemic case for our specific contextual design initiative. This became our system in focus, and our design efforts were then concentrated on setting an actionable agenda for the realization of this event.

Figure 2.3 Curating the Conditions for a…, Team 3: Designing Learning Systems for Global Sustainability, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

Chart 2.16, Team 3: Designing Learning Systems for Global Sustainability, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

Given that there are numerous pathways to address the meta-level design objective, we set the system level objective for the ISSS Conference based on the theme of Systemic Leverage Points for Emerging a Global Eco-Civilization. By setting this focus we intended for ISSS 2013 to provide both a platform for other contextual designs framed within the meta-level objective of curating the conditions for a thrivable planet, as well as to catalyze the emergence of a network of such initiatives through the specific system level focus chosen for this event. We considered that the selected conference theme would attract living cases of systemic sustainability – those which demonstrate socio-ecological innovations that span social, technological, economic, agricultural, and infrastructural domains. By focusing ISSS 2013 on the exploration of both real-world cases of systemic sustainability and theoretical models dedicated to their promotion, this event will serve to seed the emergence of a Global Living Laboratory network of such initiatives. The result of this event would therefore be the emergence of an auto-catalytic socio-technical system focused on individual projects of systemic sustainability that collectively contribute to the creation of conditions for a thrivable planet.

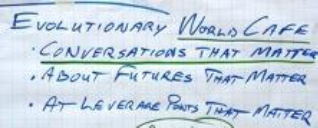

Evolutionary World Cafe, Team 3: Designing Learning Systems for Global Sustainability, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

The design we worked out for ISSS 2013 was based on the four ways of knowing described by Heron and Reason in 19971, moving from experiential knowing to presentational knowing to propositional knowing to practical knowing. Through both local and virtual conversation-based systemic inquiry, our design offers a key example of systemic socio-ecological innovation aided by collective intelligence.

Heron, John and Reason, Peter (1997). A participatory inquiry paradigm. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(3), p. 274-294.

Team 4: Towards a Common Language for Systems Praxis

James Martin , USA ( martinqzx@gmail.com )

Johan Bendz , SE ( johan@bendz.se )

Gerhard Chroust , AT ( gc@sea.uni-linz.ac.at )

Duane Hybertson , USA ( dhyberts@mitre.org )

Harald (“Bud”) Lawson , SE ( bud@lawson.se )

Richard Martin, USA (richardm@tinwisle.com)

Hillary Sillitto , UK ( hillary.sillitto@blueyonder.co.uk )

Janet Singer , USA ( jsinger@soe.ucsc.edu )

Michael Singer , USA ( jsinger@soe.ucsc.edu )

Takaku Tatsumasa , JP ( takakut@kamakuranet.ne.jp)

Jack Ring, US, jring7@gmail.com (offline support)

Photo by team member Takaku Tatsumasa, Team 4: Towards a Common Language for Systems Praxis, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

We took on the challenge of unifying the languages of “systems praxis” to help practitioners deal with the major cross-discipline, cross-domain problems facing human society in the 21st Century. The week provided a remarkable opportunity for systems engineers, systems thinkers, and systems scientists to work together to make progress on really difficult issues. Representatives of INCOSE, a new IFSR member organization, participated in the Conversation for the first time.

Given our goal of a “common language for systems praxis”, we explored both the challenges of developing common languages and alternative definitions of systems praxis, including

- “The appreciation of systems by recognizing the quality, value, significance, or magnitude of people or things as they contribute to system behaviors that lead to desirable outcomes”

- “Translating theory into action by thinking in terms of systems”

- “Recognizing, creating, and improving systems”

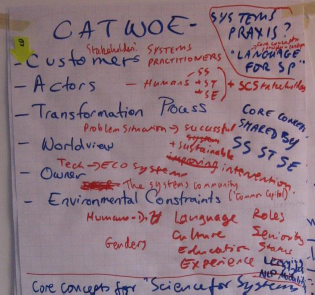

We used Checkland’s CATWOE2 approach to understand the usage, context and constraints

2 P. Checkland. Achieving ’desirable and feasible’ change: An application of soft systems methodology. The Journal of the Operational Research Society, 36(9):pp. 821– 22 for any “common language for systems praxis” (excerpts):

- Customers: We think primary customers for this work are system practitioners, and possibly tool developers.

- Actors/Stakeholders: Primary actors and stakeholders are those who work in the fields of Systems Science (SS), Systems Thinking (ST), Systems Engineering (SE), Systems Intervention (SI), and the stakeholders who are critical to their success. Benefits: Practitioners, systems integrators, consultants, and their employers will find it easier and faster to work successfully across multiple communities of practice to achieve common purpose. Students will find it easier to integrate a systems perspective into their learning and discipline practice. Managers will have a reduction in their cognitive load due to reduced project complexity. And policy makers will benefit from clarity of exposition of complex systems issues.

Chart 1, Team 4: Towards a Common Language for Systems Praxis, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September

- Transformation: We want practitioners to be able to use a “common language” (core concepts, principles, patterns, and paradigms) in an integrated systems approach in order to work with stakeholders to achieve a successful and sustainable transformation of a problem situation into an improved situation through an appropriate set of interventions.

- Worldview: We want the “common language” to be useful to practitioners and other stakeholders concerned with 831, 1985. See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soft_systems_methodology #CATWOE.

problem situations that call for solutions involving hybrid systems including Social, Technical, Economic, Environmental, Political, Legal, Ethical, Demographic (STEEPLED) aspects. - Owner(s): We want the common “language” to be adopted and owned by ”The Systems Community“ (practitioners, researchers, and educators). Initially it will be owned and curated on their behalf by the group that started this work at the IFSR conversation in Linz in 2012.

- Environmental Constraints: The language will be used by humans and machines accustomed to different languages, “symbol systems”, standards, and with different mental models, culture, experience, roles, seniority, status (power relationships), learning styles, neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) modalities, gender, education (scope, discipline, level), belief systems, and paradigmatic silos. Teams using the common language will be multidisciplinary; multi-site; multi-organizational; multi-national; suffering from spread-think and group-think; working under management pressure and complex legal, infrastructure, institutional constraints; sharing (or not) narratives and success stories, inertia, not-invented-here, collaborative/competitive behaviors. Systems developed using Unified Systems Praxis will have to satisfy constraints from the natural environment (hazards, pollutants, resources); social environment (social requirement, public acceptance, increase in population); and engineering and design constraints (laws, specifications, codes, new built & maintenance, intended lifetime, transition strategies, …)

- Our CATWOE checklist provided context for understanding how an integrated systems approach could put theories from Systems Science and Systems Thinking into action through technical Systems Engineering and social Systems Intervention. We learned that the best medium for communication across different “tribes” is patterns, and that a common language for “Unified Systems Praxis” could use system patterns and praxis patterns to relate core concepts, principles, and paradigms, allowing stakeholder “silos” to more effectively work together. We captured this vision in a figure that continues to evolve as our final report is being prepared. By using a neutral language and not “boxing in” the domains, we were able to “separate e people from the problem”. The result was a neutral map that each tribe can use to explain its own narrative, worldview, and belief system, as well as to appreciate how the various worldviews and belief systems complement and reinforce each other within systems praxis.

Our ongoing conversation is contributing content for the INCOSE Guide to Systems Engineering Body of Knowledge currently under development. Feedback from interested members of the IFSR community is welcome.

Chart 2, Team 4: Towards a Common Language for Systems Praxis, 16th IFSR Conversation 2012, IFSR Newsletter 2012 Vol. 29 No. 1 September